|

|

Empty Nest Magazine

|

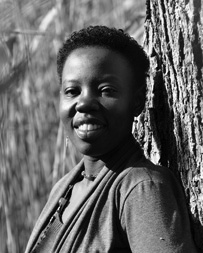

Empty Nesting, Luo Style It Takes a Village by June Gondi

The Never-Ending Brood Let me explain. Insofar as I can remember, our home has always been a home not only to my three siblings and me but also to members of our extended family. And we have a large one. My paternal grandfather had two wives, who bore him 18 children. My maternal grandfather had four wives. I am not sure how many siblings my mother has in all, but her mother bore my grandfather seven children. And even though my parents’ siblings have their own families, the vagaries of life call for them to pitch in and help one another take care of other family members who need assistance. With big families, of course, that happens often.

One Family’s Saga Then there is the case of my mother’s youngest sister, whose life choices necessitated that her four older sisters, my mother included, should step in and help raise her three children. That was about six years ago. At the moment, the two oldest girls are living with my family. One of them has graduated from high school, has taken a certificate course in nursing, and is looking for a job. Her younger sister is currently a sophomore in college, and it was in the course of updating me about the family that my mother uttered one of her familiar refrains: “I am looking for school fees for your cousin.” At the time, my cousin’s college tuition for the upcoming semester was due. To complicate things, my parents’ surrogacy extends beyond the children of their siblings. In addition to the three first cousins currently staying with them, another cousin needs their assistance as well. I call him a cousin because I don’t know how else to refer to him. His father was a nephew of my paternal grandmother, and he, too, lives with my family.

Luo Families Marriage among the Luo is of great importance, and men and women who don’t marry are considered pariahs. Married couples are required to have children. The significance of marriage and childbearing underscores a widely held Luo belief: Procreation is the most important human function. Infertility in a couple is considered a curse and is blamed on the woman. Children are considered important, so couples tend to have several children. But, because this is not always feasible, families with fewer children are beginning to emerge among the Luo.

A Perpetually Un-Empty Nest When my mother moved in, managing the household and rearing the children became her responsibility. Traditionally, women are expected to take charge of domestic matters, and this trend continues even if the woman has a career of her own. Like every working woman, my mother had to learn how to juggle the responsibilities of being a wife, mother, and career woman. Although it seems that children are always staying with my parents, this doesn’t mean that they never leave. They do. I first left in eighth grade, when I went away to boarding school. And with the exception of school and college holidays and summer vacations, I have never been back. That is because I took my first job in Philadelphia, where I have lived now for 12 years. Two of my siblings have also left, and the youngest, who still lives at home while attending college, will leave soon, as well. (She is set to finish later this year.) To we children who have left our parents’ homestead, you can add the myriad cousins, relatives, and children of my parents’ friends, who have lived with us for a time, then left, too, after they found their first jobs and were able to support themselves.

All in the Family For example, my father and his siblings hold regular family meetings, as needed, to discuss any challenges faced by family members. My father and his brothers attend these gatherings, but so do their wives and any children who have reached the age of 18. In fact, so many of us are now 18 or older that we started our own get-togethers. In addition, every year, every working grandchild is required to contribute a certain sum to the family coffers. The money raised supports the efforts of our collective parents. So, as you can see, for my family and me, the idea of an empty nest is a foreign one. And this will be the situation as long as my “family” exists—from first cousins to other members and relations of my clan, to friends of the family. Because, as they say, "It takes a village."

Links:

June Gondi is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and the Rosemont College MFA program. She teaches sixth-grade English, history, and math at Germantown Friends School. June Gondi is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and the Rosemont College MFA program. She teaches sixth-grade English, history, and math at Germantown Friends School.

|

Empty Nest: A Magazine for Mature Families

© 2010 Spring Mount Communications