|

|

Empty Nest Magazine

|

Real People Empty Nesting: Julie Longacre: Artist, Poet, or Both? By Robin Bonner

When Julie Longacre paints, she is compelled to write poetry. When she writes poetry, she is drawn to her easel. As she explained in a recent workshop, Throughout her career, Julie the artist and teacher has proved a cultural mainstay in southeastern Pennsylvania. Growing up near Reading, PA, her life took many turns—to Kansas for college, then to Williamsburg, VA, to begin her career—before she eventually came home. And, her landscape paintings have that comfortable “coming home” feel about them—a welcome respite in a world driven by civil unrest and Wall Street greed. Julie’s old barns and covered bridges adorn offices from banks to real estate developers, from Pennsylvania to California to Florida to Nova Scotia. She painted the mural in the Morgan Cancer Center of Allentown Hospital, and her work hangs in the John Deere Museum, in Iowa. She has also had several major exhibits in Canada. Finally, Julie gives back to the community by sharing some of her historic images with organizations focused on preservation.

Julie Longacre’s work makes one stop and consider the meaning of time and place: In her commissioned work, sometimes she finds it necessary to paint a restoration before it is even begun—essentially showing an historical building as it will look after it’s been restored. (She painted the Frederick Muhlenberg State House, currently under restoration in Trappe, PA.) Julie’s writings include her memoir, The Place I Keep, an illustrated book of poems and sketches, shown on her website and available by emailing Julie at CJulieLongacre@aol.com. She has also recently published the wildly popular Dirty Old Ladies Cookbook, favorite recipes peppered with memories and amusing anecdotes. It is there that Julie ties together her thoughts on joy and beauty with food. Today, Julie paints, writes, gives workshops on art and poetry, and exhibits her work. She enjoys time with her two sons and their families, including her five grandsons. You can learn more about Julie and her work by reading on, and also by perusing the Longacre Studios Website. EN: Julie, describe your early years. What do you think influenced you to choose painting as a career?

Julie, about 5, and her kitty cat.

Julie with her Argus C3 camera, Bethany College, 1962.

JL: A love story. I always had my sights set on college, but in my junior year in high school, I met a fellow classmate, Newt. I worked for his family business through my senior year. We dated two years before I realized our goals in life were very different. Devastated by the breakup, I decided to continue my education. Late in the summer and too late to get accepted into college but for the hand of fate, by coincidence a magazine arrived that contained an article about Bethany College, in Lindsborg, Kansas. Bethany, which specialized in art and music, was an outstanding liberal arts school at that time. My high school’s superintendent phoned the college and had me accepted over the telephone. I earned my degree and had two years of teaching experience before my high school sweetheart reappeared and asked me to marry him. (That was 44 years ago.) EN: Tell what it was like raising your family. How did you balance family life and career as your sons were growing up? How did you spend “quality time”?

Newt and Julie, c. 1958.

Both Newt and I were compelled to work long hours. To satisfy my creative appetite, I had my teaching and my domestic projects: I braided the rug for our living room out of wool scraps readily available at the mills. One project led to another until we moved to our new home in Barto, PA, where I began to paint in earnest. Acrylic was my medium, and balancing an artistic drive with a domestic love was the challenge. By 1971 I had two sons, a teaching career (I loved kids), and a passion for painting, which I did nights and weekends while the boys were either asleep or out in the yard exploring nature. As long as they were happy, I didn’t mind cleaning up the mess. They built dirt tracks for their toy trucks, mud was their modeling clay, and mounds of cut grass in summer provided hours of play. Indoors, I had a few tricks up my sleeve: By placing my younger son, Jason, in his high chair with a bowl of ice cream, he could finger paint with it, smear it, or even eat some. He was content, and cleaning up the mess was a small price to pay for the hour of creative bliss I gained.

Jason, keeping busy with a fudgesicle while Mom paints.

When the boys were little, I had made enough extra money from the sale of my paintings to employ a high school girl to help with chores and babysitting after school. Our home was a haven for teens whose parents supposedly “didn’t understand them.” We provided a home for them during those difficult years, and they in turn loved caring for our children, becoming part of the family.

Everyone on a farm helps with the chores: Little Newt, shucking corn.

I need to mention that all through the years I was raising a family, I kept a journal, writing about the ups and downs of the day. This helped me maintain my sanity and a wholesome sense of humor. To this day, now that my boys are married with sons of their own, they love to hear me read from these journals. My grandsons listen with interest as I relate stories about their daddies when they were kids. I can’t stress enough the value of keeping a journal. When I lecture or meet an interesting person, I stress the importance of logging their thoughts and keeping an account of each day and their reactions, then invite and encourage my listeners to do just that. How I would love to read a journal written by my mother or grandmother, if only they had kept one! Never underestimate your importance in the lives of those around you. EN: Describe your “typical day,” or if no one day is typical, then a couple of representative busy and interesting days you’ve experienced recently.

Julie, with grandsons Dylan, Daulton, and Devon (in carrier), and daughter-in-law Tee.

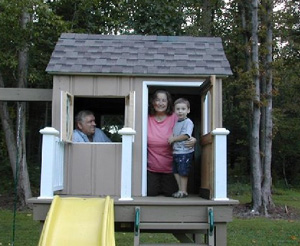

Newt, Julie, and grandson Chase in the playhouse.

Now, a typical day begins with journaling, oatmeal, and a list of things to accomplish in the studio. Seldom does a morning flow without interruptions. Keeping my head intent on the project at hand is difficult when I have to stop and refocus. When I have a serious commission, one requiring much concentration, I will move to my private studio, hidden away in the woods where I can work uninterrupted. I love caller ID, and I only check my emails at night, so I’m not distracted by a new transaction from my website nudging me in another direction. Friday: I meet my four girlfriends for breakfast. From there I stop by the studio to pick up two paintings and listen to my messages on the answering machine. I have an agenda today, so I don’t check my emails; my day is already jam-packed with meetings. I meet Robin for lunch and begin our interview. We discover a mutual interest in the way we approach a day: Both striving to live in and enjoy the moment, having experienced a similar lifestyle of channeling the surges of creative energy that drive us into a high-speed multitasking existence.

Painting of “The Speaker’s House,” as it will appear after restoration, Trappe, PA.

The vegetable soup was tasty, and I feel great: I got some of the answers correct on Jeopardy.

JL: The first seeds of the cookbook were already germinating in the early 70s when I created recipes for my family and illustrated them. About 30 years ago, I met several women with similar interests in art. We became steadfast friends (food and the artistic nature go hand in hand). Food was an integral part of our gatherings; we not only nourished our souls, we appeased our appetites. I was inspired to write “Searching for the Lost Spirit”, an essay on the joys of kindred spirits and the joy of food, which included the recipes of the breads and desserts we so enjoyed. I wrote the essay to acknowledge my gratitude to these women who brought so much fun into my life. As the years wore on, my intent to publish a cookbook with true-life stories became a reality. Being practical, I couldn’t put years of work into a project without realizing some financial gain, so I decided to name the book, The Dirty Old Ladies’ Cookbook, knowing full well that few who read the title could resist sending a copy to their girlfriends, their wives, and any newlyweds they knew, and so it came to pass. I remember phoning my husband from my summer home in Nova Scotia. After spending a month working on the book there in the quiet repose of the Cape Breton landscape, I asked him what he thought: Finish the book and go for it, or give it up and just allow family and friends to enjoy it? He said, “Go for it!” It took me another year, 24/7, to complete it. The first 500 issues were published Thanksgiving 2008, then signed, numbered, and sold, all in three days. With two subsequent reprintings, the rest is history. Writing the book was the best thing I could have done in my empty-nesting years. I recalled my childhood experiences, but the stories practically wrote themselves once I tapped into the lost recesses of my memory. Humor wove its way through the manuscript, as I recalled all my funny, misfortunate episodes in the kitchen. I highly recommend writing your stories and keeping your family recipes for those you love, who will follow you.

The Dirty Old Lady Cookbook tea party, March 2011.

After cleaning up the mess, I decided there were more civil means to solving an argument. Recently, I decided to have a “Dirty Old Ladies’ Tea Party.” Ever since the book hit the stands in November 2008, I’ve wanted to have a party, not to buy anything, but to exchange laughter and ideas, and to enjoy the company of other kindred spirits. In my business, I meet people, women from all walks of life, and many I wish I had the time to know better. I invited about 30 to my party. We decorated with silk roses and passed a basket of laughs around the table that contained quotes of wisdom and jokes from everyday life. All the women in the group had grown, married children, so we had much in common besides our creative, care-giving personalities. The menu comprised recipes from the cookbook, including chocolate-covered strawberries, Wedding soup, and decadent chocolate cake with Longacre’s Cherry Garden Ice Cream. Catherine made the favors of handmade, painted candy boxes, and everyone went home with smiles and requests to do it again. EN: How did your life change after your children grew up and left home? How do you think you are still growing professionally, and as a person? What advice do you have for new empty nesters in meeting the challenge of finding a “life after kids”?

JL: My life didn’t change much after the kids left. I was still me, but I had more time to explore the many channels of creative output available to me. I still get a chill when the phone rings late at night. My prayers always include the kids, their families, and the other set of grandparents. All of the experiences of the past embellish those of the present. I don’t seem to move forward without a backward glance of gratitude. I find it difficult to embrace all that I’ve accomplished, We’re all born with a creative seed. When that seed germinates into motherhood, we are destined to a career that nourishes our creative spirits within the boundaries of domesticity, and we find solutions to an uncharted menagerie of circumstances for which there is no guide. My advice to the new empty nester and to the “Nanas” out there is to embrace each moment, be it filled with laughter or swept away with tears. Don’t question a notion, an idea, or a suggestion. If you think it, do it! Become an explorer of your own inner desires. There isn’t a man or woman who can’t paint, write, or cut a picture out of a magazine and paste it into a scrapbook of memories. You are the sum total of your experience—write it down and pass it on!

Robin Bonner is editor of Empty Nest. For more about Robin, see About Us. |

Empty Nest: A Magazine for Mature Families

© 2011 Spring Mount Communications