|

Caring for Aging Parents

Available Resources:

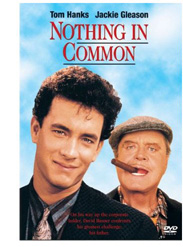

A Review of Film Nothing in Common

by Clare Gassler Frey

The Film

Nothing in Common (1986) is not a new film, but, it raises issues perennial to adult children of aging parents. In viewing it, we experience the struggles of David Basner, a typical American adult child (played by Tom Hanks) abruptly faced with the responsibilities of caring for his aging parents. The average American demographic has aged over the past 30 years, so many of us know these physical, mental, and emotional struggles first hand.

Nothing in Common (1986) is not a new film, but, it raises issues perennial to adult children of aging parents. In viewing it, we experience the struggles of David Basner, a typical American adult child (played by Tom Hanks) abruptly faced with the responsibilities of caring for his aging parents. The average American demographic has aged over the past 30 years, so many of us know these physical, mental, and emotional struggles first hand.

Basnerís mother, Lorraine (played by Eva Marie Saint), needs him first. David learns that she has left his father after a long marriage. Lorraine is not Davidís problem, however. He is a little concerned about her uncertain future, but he feels she can take care of herself. Next, David faces his father, Max (played by Jackie Gleason). Max responds with hostility and withdraws when David tries to talk to him about his role in causing the separation. Finally and most disastrously, David discovers his fatherís gangrenous feet, caused by self-neglect of his diabetes.

The film is set in the 1980s, but Davidís plight would be familiar to many caregivers today. His parents are separated, one is chronically ill, and he has no siblings to help with caregiving responsibilities. Add to that other common issues: David works. Heís busy. He has his own difficulties. Heís unprepared for caregiving and in general feels unsupported in that area.

In the midst of these challenges, American gerontologists ask, "Should families provide for their own?" Letís explore this controversial question as it applies to the fictitious Basner family.

Aging and the American Family: Who to Turn To?

When in need, most American elders turn to their families. Max finds that he needs help because of a health problem. He would rely on his spouse, but because of their deteriorating relationship, he cannot. Elders who live alone typically turn to their children, most often to the eldest daughter. This elder has no daughters, though—just one absent son who is a lot like his father and not likely to be of much help. The exchange theory of aging states that interaction in families is based on reciprocal balancing of rewards for good deeds performed for one another. That theory is somewhat hampered here: The aloof father never cared for his family emotionally, and now his family canít, or wonít, help him.

Like his father, David has problems with intimate relationships. He finds personal gratification in a successful career and an unattached sex life. So, David has no wife to help him care for his father. Gradually, however, he gains some insight into what went wrong in his parentsí relationship and begins to value Donna Martin (played by Bess Armstrong), his old high-school girlfriend. She is now his friend, but he begins to see her as more than an occasional "emotional pit stop." Caring and supportive, she accompanies David to the hospital during his fatherís surgical stay. If they marry or remain close, she may take on many of the caregiving responsibilities when David returns to work.

For the time being, however, David chooses to fulfill customary filial responsibility, that is, the obligation of adult children to provide care for aged parents. He chooses to take a leave of absence from his job to care for his recovering father. Because he is financially successful, David might easily have hired a nurse. Despite his past lack of involvement with his parents, though, he instead takes on the primary caregiver role. He does so with backing from his mother, his old girlfriend, and perhaps some unnamed formal support services.

Abandonment or Independence?

David resides in the same city as his parents, but as an adult, he went his separate way. Now, he develops a relationship with both his mother and his father that could be termed "intimacy at a distance." He visits his motherís new apartment; he checks up on her late one night after sheís been on a tense but enjoyable first date. He takes his father out to a jazz club, buys him groceries, and is vigilant in the hospital when he undergoes surgery. And, he does all this while maintaining his own, separate residence.

For the Basners, independence in future living arrangements is implied. (Typically, elders in the United States live apart from their grown children.) David announces that his father will be okay on crutches after a time, meaning that he will be able to function on his own. He may move in with his father for a while, but there is no mention of him giving up his apartment. Nor will Max move in with him; Max has always led a solo life. Even Lorraine takes up an independent life with a steady job and an apartment of her own, although she had never worked outside the home. The scenario fits the American expectation that adult offspring keep their own, separate residences.

All caregiving, even at a distance, is stressful. The film illustrates this stress in the scene in which David seeks emotional refuge with his old girlfriend, Donna. He is close to collapse, and without sufficient support or self-care, that collapse would be inescapable.

Family Responsibility

In the film, Lorraine Basner portrays spousal responsibility. However, she concedes that she cares for Max but that a continued marital relationship with him is impossible. She contributes, unseen, from a distance. She cleans and stocks Maxís apartment, so all will be in order when David brings Max home, but she tells David that she will not be coming back. She tries to prepare David for the responsibilities that she cannot take on.

Because of his financial success, David is able to take an unpaid leave of absence from his job. In doing so, he begins to discover valuable emotional resources as well. Surprisingly, filial responsibility swells in David. He is visibly proud when Max remarks that his son is the last person he ever thought would be there for him.

Long-Term Care and Government Entitlements

Social Security, Medicare, and Disability

At the filmís onset, Max is employed. He loses his sales job after his wife leaves him and just before his son discovers his health issues. Despite Davidís optimism that his father will only need help for a short time, complications of diabetes, such as amputation and blindness, could easily require professional long-term care. Max is likely not yet 65 years old, so Social Security and Medicare benefits, which are strictly age-based (rather than need-based) government entitlements, would not yet apply. If Max should become disabled, however, he might qualify for disability benefits.

Paying into the Government Safety Net

There is another consideration. Even if Max is 65, he may never have paid into Social Security and Medicare during his years of employment and therefore would not qualify for the safety-net retirement income benefits of Social Security or the elder healthcare benefits of Medicare. About 95% of all workers pay into this safety net and eventually reap their benefits. A salesman, however, depending on his employment situation, might not have paid into the fund. In any case, Medicare covers very little long-term care.

Medicaid

Medicaid, a need-based program, does cover the majority of long-term care for the elderly. This includes nursing home care. Originally, Medicaid was implemented to assist poor families. Today, however, the majority of Medicaid funds are used to supplement the expenses of long-term care for poor elders, either in a nursing home or hospital, and other medical and rehabilitation services not covered by Medicare. If Max is poor enough, or becomes destitute in the future, Medicaid would be available to him. The film sheds little light on such issues as they relate specifically to Max, but the issues are raised for the rest of us to explore.

Financing Long-Term Care

Considering Spend Down

The film paints Max as a carousing salesman who smokes cigars before breakfast. He does what he wants•not necessarily whatís best for him. Chances are he hasnít much savings or even a pension. He has no job and probably no health insurance. Medicaid, the need-based government entitlement program, requires spend down of assets. Spend down is a way to qualify for Medicaid. Before Medicaid will pay for services, an older person must spend down, or deplete almost all personal assets and apply all montyhy income, except for a small personal allowance, toward the cost of nursing home care. After spend down, however, if Max and Lorraine are still legally married, little money would remain for Lorraine, and there would be no inheritance for David.

So, letís say caregiving becomes too much or too long term for David. Then, if Max is left on his own, he will have to use up most of his savings to qualify for long-term care under Medicaid. Even after spend down, Max would be forced to move into an institution. In 1986, Medicaid long-term care was always rendered in an institution. On the other hand, David is very successful in his career and might be willing and able to finance Maxís long-term care if he still requires care when David needs to return to work. Todayís elders have additional options.

Community Residential Care

Since the late 1980s, in response to a need for more cost-effective long-term care, community residential care (CRC) has risen dramatically. CRCs offer group housing with additional services, such as meals, basic health care, and some personal assistance. Examples include assisted living and adult foster care. The lower cost of CRCs compared to institutions has made them a more desirable option for states with growing numbers of frail elders needing public assistance. Medicaid waivers for CRC options are now available in some states. In fact, the national trend is away from traditional nursing homes and toward CRCs.

Medigap

Today, some elders are not poor enough to qualify for Medicaid, which would help fill in the gaps left by Medicare coverage. For them, there is private long-term care insurance. It is called Medigap. Elders without Medicaid are encouraged to purchase such a policy, which could cost from $50 to $250 per month. For further information on Medigap, call the Medicare hotline (1-800-MED-ICARE; yes, you dial all the digits) and ask for their "Guide to Health Insurance for People with Medicare." Some elders choose to continue their employer-sponsored health insurance plans that serve the same function.

Medicaid Planning

Retirement takes some planning, and this father is not a planner. Most likely, he did not squirrel away any hidden cache to avoid spend down of his assets. Further, this son had been absent from his parentsí lives and also lived from day to day. So, it is unlikely that he advised his father to transfer any savings to him. To be fair, the idea may not have occurred to him. In the 1980s, there were no elder law attorneys to assist in circumventing spend down through divestment planning. Even if there had been, the sad reality is that the father did little planning before his life began to crumble. On the other hand, divestment planning through elder law channels is controversial. Some believe that low-cost health care is not a right, that it should only be avauialbe to those in financial need. They believe it is immoral or unethical to find ways to pass money on to one's children, to hide money, and so on. They say that each of us should bear whatever burden we can towrd paying for our own old-age long-term care&8212;especially in light of the growing number of elders and the rising cost of health care. Universal health care would end the fuss, but that is not yet a reality.

Nothing in Common paints just one scenario of what can happen when family bonds are strained and the future has not been planned for. But, if we are informed, we can do better. Visit the Medicaid and Social Security websites for more information on financing health care for the aging.

For More Information:

Medicare/Medigap

Wikipedia: Medicaid

Elder Law & Medicaid Services

Health: Medicaid

Medicaid in New York State

Clare Gassler Frey is a certified gerontologist. She holds a certificate in Gerontology Studies from Assumption College in Worcester, Massachusetts. Clare did her undergraduate work at the University of Delaware, where she completed a B.S. in Physics. She has two grown children, a son and a daughter, and a 15-year-old son, who lives at home. Clare looks out for her own mother, who lives several states away. She is shown here with her Aunt Margaret, who is 91 and lives independently. Clare Gassler Frey is a certified gerontologist. She holds a certificate in Gerontology Studies from Assumption College in Worcester, Massachusetts. Clare did her undergraduate work at the University of Delaware, where she completed a B.S. in Physics. She has two grown children, a son and a daughter, and a 15-year-old son, who lives at home. Clare looks out for her own mother, who lives several states away. She is shown here with her Aunt Margaret, who is 91 and lives independently.

|